Steno Signals #204 - Is the Trump project still vastly misunderstood?

Ahead of a new tariffs-intensive week, we’ve asked ourselves whether the Trump project remains misunderstood by many. Where is the MAGA project heading—and how should we allocate accordingly?

***Action Required to Continue Receiving Steno Research

Steno Research is joining forces with Real Vision! To continue receiving our research, you’ll need to sign up through Real Vision.

If you’ve prepaid for a full year on Substack, please contact us at info@stenoresearch.com, and we’ll guide you through the process. For everyone else, please visit https://app.realvision.com/pricing to sign up.

We look forward to seeing you over at Real Vision! ***

Welcome to my weekly editorial, where I aim to look a bit further ahead—and discuss the most pressing issues shaping the world of macro.

I had a good chat with one of my talking partners that I respect the most in the macro business about how misunderstood the Trump project still is—both outside and, to some extent, inside the US (you know who you are).

In light of the tariff-fueled week ahead and the interesting shifts in labor market dynamics, I’ve spent most of the weekend reflecting on what this project truly represents—and how one should allocate accordingly.

My sparring partner made the case that Trump is largely following a “William McKinley” playbook. Admittedly, McKinley wasn’t top of mind for me, so I took some time to revisit what he actually did during his 1897–1901 presidency. After digging into the topic, I think there’s actually some merit to the analogy.

McKinley “re-industrialized” through tariffs, pursued territorial expansion (e.g., Guam, Hawaii—are you watching, Greenlanders?) and was a firm advocate of sound/hard money via the gold standard. Those priorities aren’t too far from Trump’s main objectives—though, of course, there are major differences in both the economic backdrop and the relationship to “sound money.”

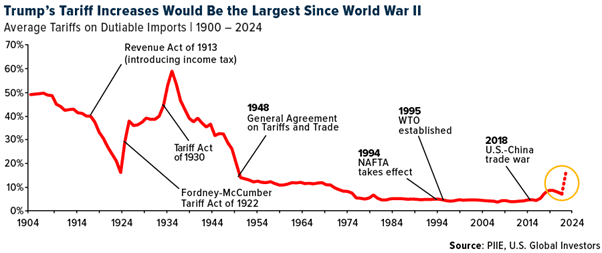

What’s interesting is that McKinley’s high tariff regime persisted until the introduction of income tax in 1913 (see chart of the week). One of my medium-term theses is that AI will erode the effectiveness of income tax as a revenue tool for governments. That could force a major pivot back toward taxing goods crossing borders—especially as we move toward an inevitably more digitized global economy over the next five years.

So, ahead of a week filled with tariff headlines, potential trade deals, and everything in between, I think it’s wise to once again cement the point: tariffs are here to stay. It makes a ton of sense—both from a geopolitical and a treasury perspective.

The real question is: are tariffs bearish or bullish? And more importantly—how do we allocate?

Chart of the week: Tariffs are here to stay

The shift in the relative attractiveness of tariffs versus income tax as a revenue generator has been underway for a few years. For Trump, this is probably not the most important reason, but the underlying economic project—designed by Bessent and Miran—includes a logic that is linked to the tectonic shifts seen in the labour market over the past 12–24 months.

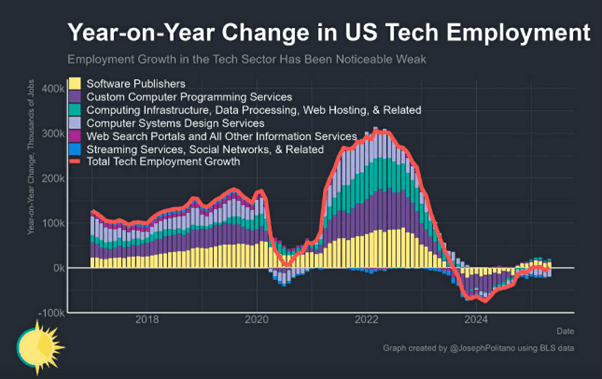

To begin with, I guess most people can agree that tech adoption is exponential, but what’s new is that the adoption/development is no longer a net job addition (in the sector), but rather at best a flat-liner. So more tech adoption does not require more people working in tech. We’ve obviously seen how Microsoft and Salesforce (to take two vocal examples) have been laying off entire departments after having AI’ed their way through the development work.

In my opinion, this serves as a tremendously interesting precursor of the shape of the labour market over the coming years. AI holds the potential (in contrast to many former technological advances) to permanently lower the participation rate in the economy. And while Trump is not necessarily subscribing to this view himself, many of his allies are—including the whole range of tech people involved in his administration, who are still planning some sort of tech-based light coup d’état (meant in a mostly positive way), as far as I can judge.

Chart 1a: No growth in tech employment (chart borrowed from Joseph Politano)

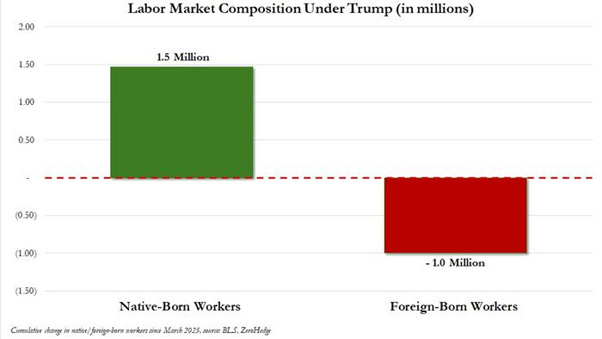

On top of the flatlining job creation in tech, we are starting to see the real impact of Trump’s border and immigration policies.

The labour force is simply shrinking (at least since earlier this year) due to ICE efforts to return illegal aliens to countries outside the US, and the participation from domestic versus foreign-born workers has seen a major shift in recent months as a consequence. This is probably the part of the Trump playbook that is most well understood—and probably also the biggest obvious success so far.

What’s more important is that this is also a way of preparing the US labour market for what’s ahead. Fewer jobs due to automation equals a smaller need for foreign inflows of labour. At the same time, fewer jobs are needed per month (in the NFP) to maintain a low unemployment rate—which is also why the NFP/unemployment statistics are likely to be vastly misunderstood by consensus economists in the coming months and quarters.

Chart 1b: The tectonic shift from the Trump border policy (Chart borrowed from Zero Hedge)

So if the tariffs are here to stay, and the geopolitical landscape is one of regionalism—with China, Russia, and the US “splitting the world between them”—what are we to expect from asset markets in such an environment?

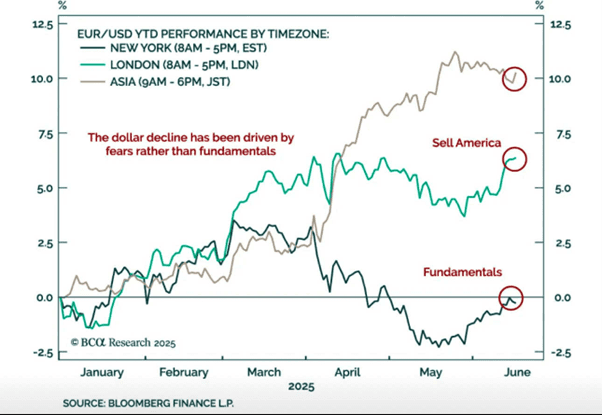

First, this strategy has certainly led to a material anti-US(D) allocation trend outside of US borders, especially when it comes to currency markets. Take a look at chart 2a, which I’ve borrowed from my good friends at BCA Research. The selling of USDs almost solely happens outside of the US trading session, indicating that Asians and Europeans are behind the offloading—which makes sense, given the hints dropped by Trump’s trade negotiators throughout this whole tariffs/trade process.

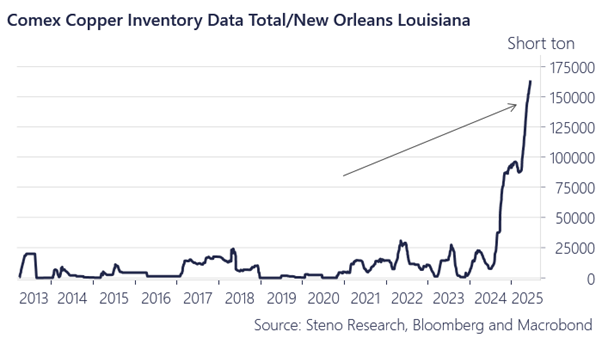

Second, this strategy has led to incredible shifts in the warehousing of metals (and other strategically important resources). Take a look at the front-loading of tariffs seen in, e.g., copper (chart 2b). Assuming that we will see more metals/commodity-specific tariffs—which remains very likely—we are also likely to deal with a much less geographically agile commodity market thereafter.

It speaks in favour of periodical scarcity of important resources, and a much larger focus on strategic stockpiles, which generally favours a very bullish take on commodities over the next 1–2 years—especially taking the USD trend described above into consideration.

This is, by the way, fairly reminiscent of what happened under William McKinley more than a hundred years ago, for what it’s worth—even if such a study should be seen in light of the big changes since.

Chart 2a: Only foreigners are selling USDs (Chart borrowed from BCA Research)

Chart 2b: Tariffs impact commodities to a large extent

The big difference between McKinley and Trump is, in my opinion, the relationship to sound money.

To me, Trump is a big “debasement guy”—also given his vested personal interests in being long gold and digital assets.

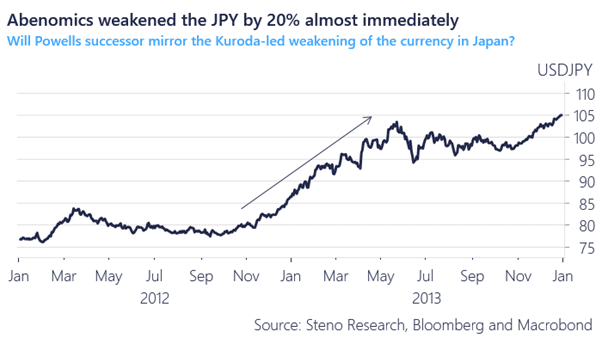

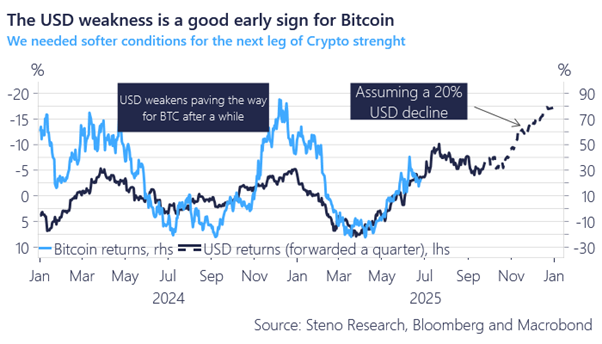

The big beautiful bill, paired with the focus on trade deficits, is a USD-negative cocktail. And if USD weakness is further fuelled by a Kuroda-like hiring for the Fed chair job, it may intensify the need for sound money (gold, Bitcoin—and the likes) for portfolio/investment purposes.

A weak USD is a prerequisite to solve the imbalances created by former administrations over decades, and that is also an obvious part of the Bessent/Miran playbook—even without it being listed as an explicit target.

You’re not going to get foreigners to fund the current debt/deficit without a much weaker USD as a starting point (makes it easier for foreigners to accumulate USDs over time). So when foreigners flee USDs, I have to state that this is by design from the current administration. The Mar-a-Lago Accord is telling you exactly that.

The big surprise for the consensus crowd just ahead of us is that the US economy will make a pretty decent comeback amidst all of this. Tariffs are (temporarily) bullish in that regard.

So yes, the Trump project remains vastly misunderstood by many. Tariffs are here to stay, as they will become increasingly obvious revenue streams in an environment where AI weakens labour participation. US exceptionalism will likely return—except in FX markets, as a consequence. Own debasement bets, both in commodities and digital assets, and expect US equities to outperform peers again from here.

Chart 3a: What if Trump copies the JPY policy of the 2010s to address the debt?

Chart 3b: Bitcoin to double if the USD weakens another 20%

Chart 3c: The US will make a roaring comeback outside of FX markets

Best read in a while